Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia "Type / Cast / Thrill.", 17 February – 11 April 2021

In Hollywood parlance, “typecasting” commonly describes the process by which particular actors are being cast for, and thus become increasingly identified with, a specific character. As a consequence, the respective actors are typically forced to repeatedly appear in similar roles, thus rendering it nearly impossible for them to perform any character of more complex nature. Driven by marketing strategies and commercial instincts, this institutional practice of typecasting also fuels the audience’s expectations informed by (sub)cultural codes, spectatorial experience, and inherent discourses. Through the creation of characters and— inevitably—stereotypes, the film industry becomes a realm in which prejudices, clichés and expectations become manifest and deeply embedded in the structures of the everyday.

Taking these processes as a starting point, the exhibition ‘Type / Cast / Thrill.’ brings together new bodies of work by Germany-based artists Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia who call into question the practice of typecasting within the expanded field of culture. Here too, visual artists are frequently confronted with supposedly fixed notions of identity inflected by gender, race, class, or national difference. An attempt to undermine these projections, ‘Type / Cast / Thrill.’ stages a dramaturgy that radically rejects this idea, conjuring up utopic visions and transitional spaces in which the categories of the existing canon may be overcome and reconfigured.

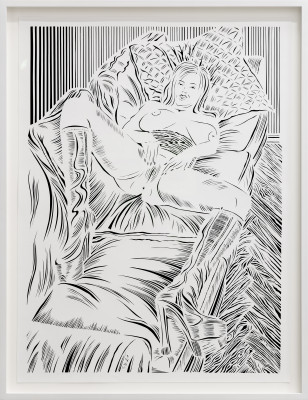

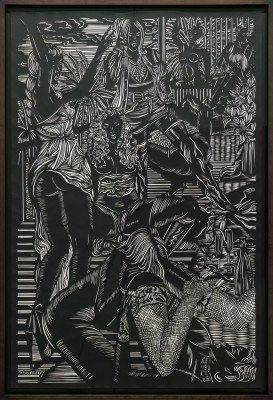

While, etymologically, the noun “type” describes an emblem or general character of sorts, the verb “cast” bears multiple meanings, among them, that of pouring liquid material into the cavity of a mold—a process often considered one of the most esteemed acts of creation (far too often male-connoted) within dominant art history. Whereas sculpture, in its most classical form, has served the tradition of three-dimensional representation of forms in space, the bodies present in the works of Yakovleva and Grafia occupy and re-inscribe the two- dimensional surfaces of canvasses, aluminum sheets or paper and—rather than being cast or molded—emerge in the process of cutting or painting.

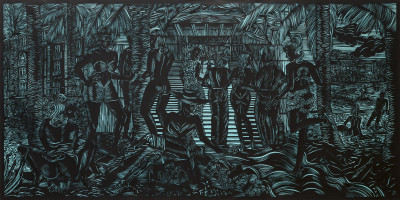

Take, for instance, Sonja Yakovleva’s monumental papercut Festival de Cannes (2020), displayed alongside three papercut-portraits of female nudes, which echoes the large dimensions of 19th-century historical paintings. Borrowing its imagery from porn movies and magazines, Festival de Cannes is a libidinous take on the tradition of the celebrated film festival that has been but one of many battlefields in women’s struggle against the misogyny and sexual violence at the heart of this industry. In the wake of the #MeToo movement in 2017, the Festival came to public attention amidst claims of sexual assaults taking place in Cannes and was exposed as complicit in the structural biases of the film industry. In Yakovleva’s very rendering of the festival, its headquarters were taken over by female protagonists and transformed into an orgy-like scene populated by a multitude of naked or scantily dressed women. In a palm-lined setting, the women give in to sensual pleasures celebrating what might be a victory over patriarchy—whose walls have been crumbling for years to ultimately collapse. The porosity of these walls is echoed in the materiality of the work resembling a field of debris: with layers of black paper punctured by meticulously cut holes that open a space for female struggles. Situated at the threshold of art and handicraft, Yakovleva’s work may be understood as an emancipatory play between the absence and hyper- presence of “femininity”, a utopic celebration of the yet unseen, and an alternative reality in which women are no longer subjected to the patriarchal stratification enforced by mainstream culture and discourse.

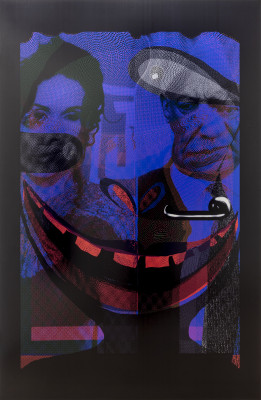

In a similar way, Nicholas Grafia’s work addresses the plight of women and people of color in the film industry through the means of painting and digital print. A prominent example of these struggles, and the main protagonist of Grafia’s new body of work, is the US-American actress Lisa Bonet, best known for her role in the seminal 1980s sitcom “The Cosby Show.” Co-created by and starring the comedian Bill Cosby (then celebrated as “Americas’ favorite dad”, later convicted of a number of sexual offenses in 2018 and incarcerated since), the show’s portrayal of a successful, black middle-class family was often praised for breaking racial stereotypes and introducing new perspectives on African American lives in mainstream culture.

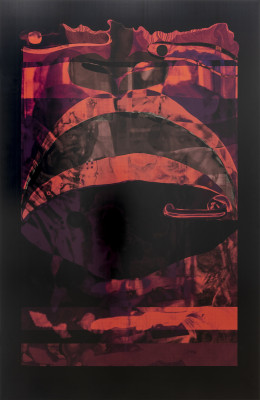

Loved by the audience for her role as Cosby’s TV daughter, Bonet was soon subject to criticism from both her character’s “creator,” Bill Cosby, as well as her audience for taking on new roles, more explicit in nature and supposedly jeopardizing her image—and that of the entire show. Translated by the artist into both canvas (Dead End Angel, 2021) and aluminum sheets (Gaze Face I and II, 2021), Bonet’s case seems symptomatic for the constraints sexualized and racialized bodies are subjected to within and beyond the entertainment industry. Digitally printed on aluminum sheets and hung on hinges attached to the gallery walls, the uncanny works Gaze Face I and II are reminiscent of doors or gateways, suggesting a space of transition between the intertwining realms of fact and fiction. Another case in point, the painting Cleavage Control (2021), is also exemplary of the artist’s inquiry into the limited narration and stereotypical representation of black masculinity perpetuated through mainstream culture. Inspired by a film still of Cosby’s TV son Theo, the protagonist’s body is touched and reached out for by ghostly hands and oversized arms—a monstruous manifestation of the audience’s controlling gaze, their unforgiving judgment and expectations.

Often drawing on a visual repertoire borrowed from pop culture, magazines, pornography or film, the works of Sonja Yakovleva and Nicholas Grafia find their commonalities in their continuous investigation of structural injustices and conventions informed by gender and race. By using the film industry as a blueprint for their works, the artists confront the viewer with dominant power relations and stereotypes often legitimized through the means of historicity or cultural production. Blurring the lines between “high” and “low culture,” fact and fiction, visibility and invisibility, Type / Cast / Thrill. reveals the fragility of these transitional spaces in which the undoing of stereotypes and tokenism may turn into a thrill of joy—or horror.

Text by Fanny Hauser